Dirt

Like coding languages themselves, the way software is developed has changed over time. It's interesting to note these changes have often aligned with major changes in the trends of the software delivery mechanics. In the early days the way users got their hands on new software was to purchase a physical hardware device, like disks or CDs. Due to this delivery model, software development was designed to accommodate long cycles that mapped to hardware design, fabrication, and validation intervals. Waterfall complemented this staged process very well.

As packaged software began to decouple the delivery of software from the procurement of hardware, there was a shift in thinking around how to best deliver software. Many realized software development could move faster than hardware cycles. So teams looked to incorporate this into the waterfall delivery model by leveraging the validation stage to provide feedback through beta testing or early access programs. The goal was to maximize customer value; but because this cycle didn't start until the validation phase, there was a limit on the changes that could be affected.

Agility and stretching

This desire to get feedback and incorporate change led to the most basic premise of Agile and Scrum delivery models. Both adopted the idea that you should have a course set and then break down the movement towards that goal into small changeable tasks or stories. This was a huge advantage to teams that adopted these models because they could make minor course corrections on their journey towards the big picture.

Meanwhile the folks doing waterfall had to make one of two equally bad choices—stay the course and wait for the next cycle, or abandon all the work and development effort that had gone in the wrong direction. The second option typically meant teams were unable to deliver any additional value to existing customers, and would probably have difficulty raising additional capital for research and development. This is the primary reason we had to live through so much horrible software in the 1990's and 2000's.

Of course—like all technology trends—as soon as we start to see mass adoption, the next major shift in the industry is already happening. This time, it was the movement from packaged software to Software as a Service (SaaS). Once the application or service lived on the cloud, a few things changed in the dynamics around software delivery.

First, there was no longer a physical delivery of any kind. This meant software could be updated at any time or pace without having to worry about getting the updates to the customer. Teams were delivering updates continuously, and customers consumed the updates immediately. But immediate updates also meant there was immediate exposure to bugs or errors. The risk here was the finding of bugs always took longer than the fixing of bugs.

Flywheels are for the young

As teams moved to a Continuous Delivery model they required infrastructure that could mitigate the risk of shipping buggy code. This is when teams started to turn to the old technique of feature flagging to separate the act of code deployment from the actual release of features. Developers were turning features on/off in production without redeploying code. Release a feature, encounter a bug, turn the feature off, fix the bug, deploy a fix, turn the feature back on... keep customers happy.

The next change that came about was actually two architectural changes at once—micro-service with globally distributed apps and data science entering the application delivery process. These two trends changed the way teams wanted/needed to deliver software again.

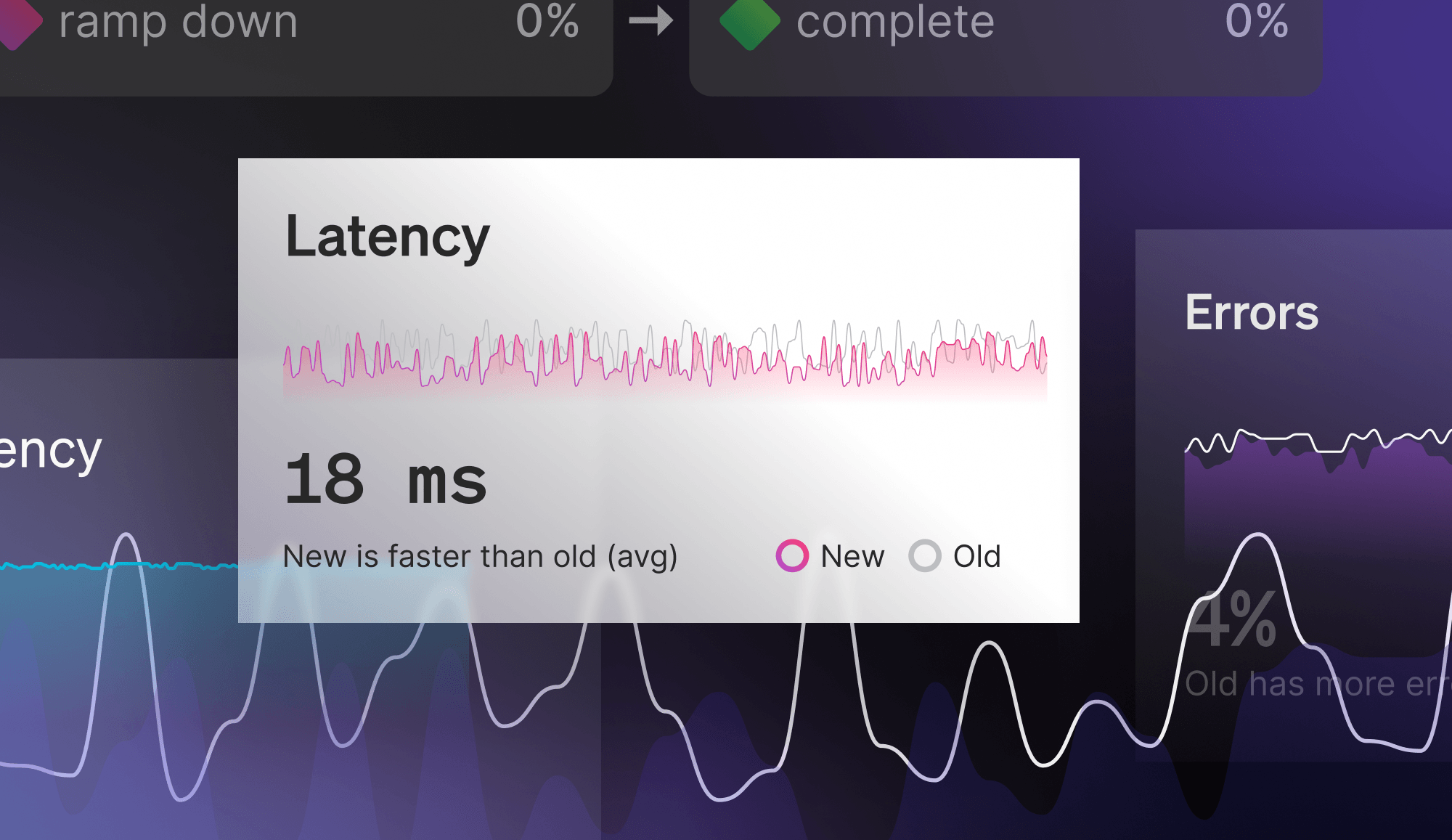

Micro-service and global distribution meant that there was a desire to isolate changes and the population impacted by those changes. Roll out a new feature to Australia first and see what adoption looks like. Maybe make some changes prior to rolling out to the EMEA market. Or maybe you want to make a change to your message queueing service but want to limit the impact to a small cohort of users. Either way, development teams and operations teams started to look to data science teams on how these partial rollouts were being received and adopted.

Sphere of Influence, or Blast Radius

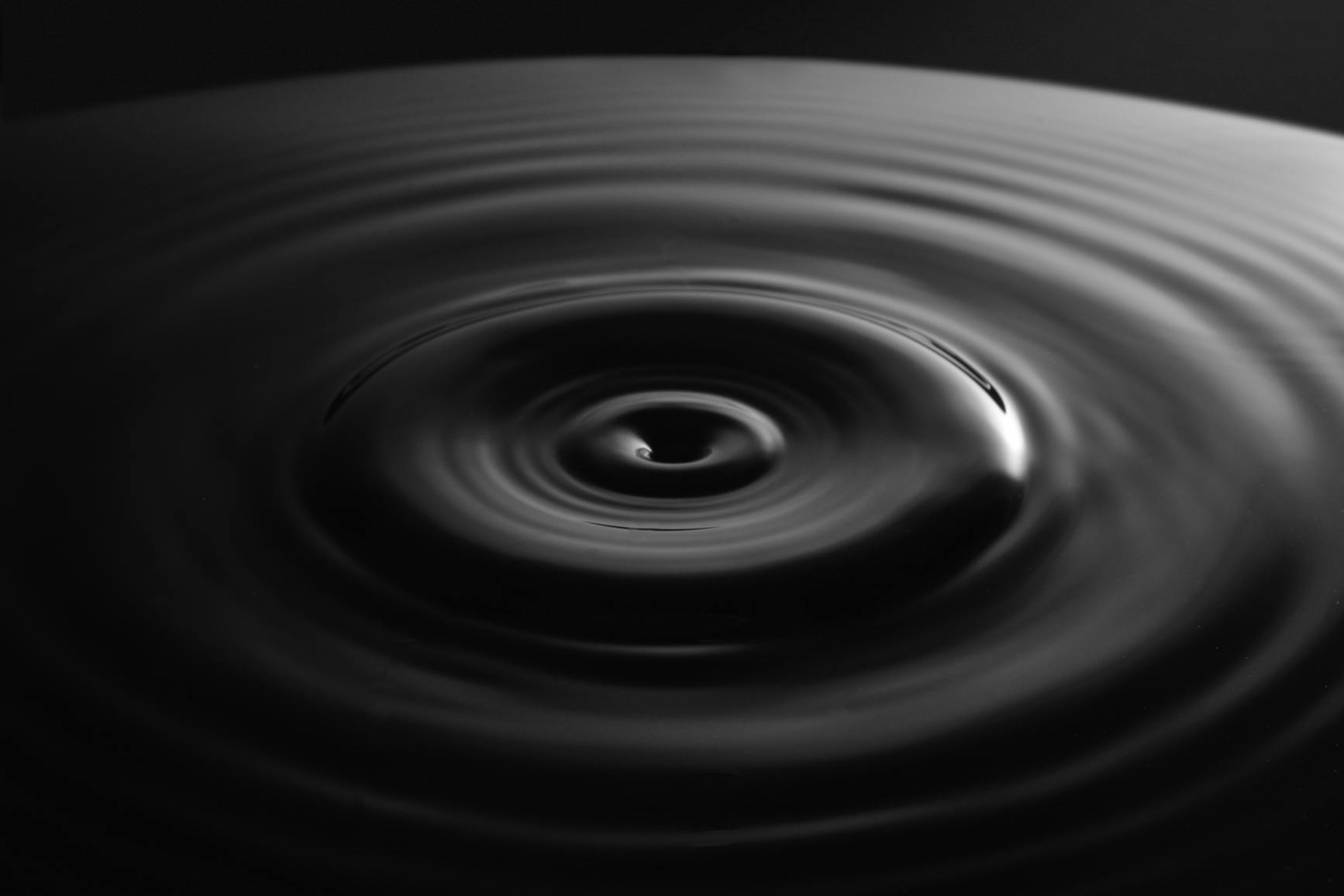

This type of Progressive Delivery starts with the premise that the release of features or updates is going to be staged in a way that manages the impact of changes included. If the release of new code is the epicenter, each new cohort that is exposed represents the increasing blast radius spreading out from that initial impact. Microsoft has been speaking about this approach for a while, and helping teams adopt the right tools to benefit from this approach.

In order to be successful in this delivery model teams need to have a system that manages the separation of code deployment from feature release, as well as control of the release, like a valve or gate that you can slowly open and close. Along with these control points there is the need to have feedback (event) data about how these various features are being accessed and consumed.

But wait, isn't that just CD with a new name?

For teams that have been running a Continuous Delivery pipeline for years this will feel like a natural progression—as it should. Many of the core benefits, tools, and mechanics remain the same. The primary distinction is the incorporation of a ‘built-for-failure' mentality.

On the side of development, the value is all about speed and risk mitigation. By starting all new development with a feature flag, code can immediately be checked into production with zero risk. This allows developers to move faster, and changes/updates to be done more independently. It also allows new or junior developers to push to production early in their onboarding, understanding flag-first development as a best practice for speed and safety.On the business side, Progressive Delivery involves two core changes in the delivery model:

- Release progression - progressively increasing the number of users that are able to see (and are impacted by) new features (e.g. Stage 1: visible to developers only; Stage 2: visible to developers and beta users; Stage 3: visible to more users; Stage n: visible to everyone)

- Delegation - progressively delegating the control of the feature to the owner that is most closely responsible for the outcome. (e.g. Stage 1: Release owner = dev. Stage 2: Release owner = PM; Stage 3: Release owner = Marketing; Stage n: Release owner = Customer Success)

An important point about delegation: while the initial implementation likely involves both the assignment of responsibility as well as the need for manual approval or action, the goal should be to base all of the delegation changes or release progressions on criteria and use metrics and event data to automate the transitions.

Continuous Delivery enabled people to fail fast, but the tools for continuous integration and continuous deployment did not have the inherent safety valves and feature flags to protect the service and the consumer. Those protections had to be added in a bespoke fashion by individual teams. Often, it was the case, that multiple teams within a single company created their own. This has led to a mess of overlapping systems that at best slow down the pipeline, and in the worst cases cause cascading failures.

Progressive Delivery incorporates this ‘built-for-failure' model through the use of feature flags and the introduction of a feature management platform that can consolidate all the control points into a single interface useable across organizations of any scale. This is a key distinction of Progressive Delivery. While Continuous Delivery can be done with or without the use of a feature management platform, Progressive Delivery requires this aspect of control.

Pictures, or it didn't dappen

For many, this is not a change from what they are currently doing. Teams like IBM, Microsoft and Target have written and talked about how they are making “Continuous Delivery ++” work for them. But as James Governor from Redmonk puts it in a recent post:

“I have been waiting for a term to emerge to describe a new basket of skills and technologies concerned with modern software development, testing and deployment. I am thinking of Canarying, Feature Flags, A/B testing at scale. Advances in approaches to application and service Observability. On the technology side, Kubernetes and Istio bring new management challenges, but also opportunities – service mesh approaches can enable a lot more sophistication in routing of new application functions to particular user communities.

…

Continuous Integration/Continuous Delivery has been extremely useful in taking us forward as an industry. CI/CD is the basis of everything good in modern software development. But I do feel there are some new aspects and practices that we don't currently have a name for.”

It's exciting to see how teams are starting to use tools to increase the velocity of their delivery while at the same time isolating risk based on readiness of the code and features. And I look forward to seeing how this software development model can help teams build better software.

.png)