There comes a time in every developer’s life when you realize you need to migrate from one database to another. Maybe you started off with MongoDB, and it was great while your app was small, but it just can’t handle the load now that you made it to the big leagues. Maybe it’s time you bit the bullet and put that huge events database in DynamoDB (or Cassandra, or … ).

Moving databases is no small task, but it doesn’t need to be so risky.

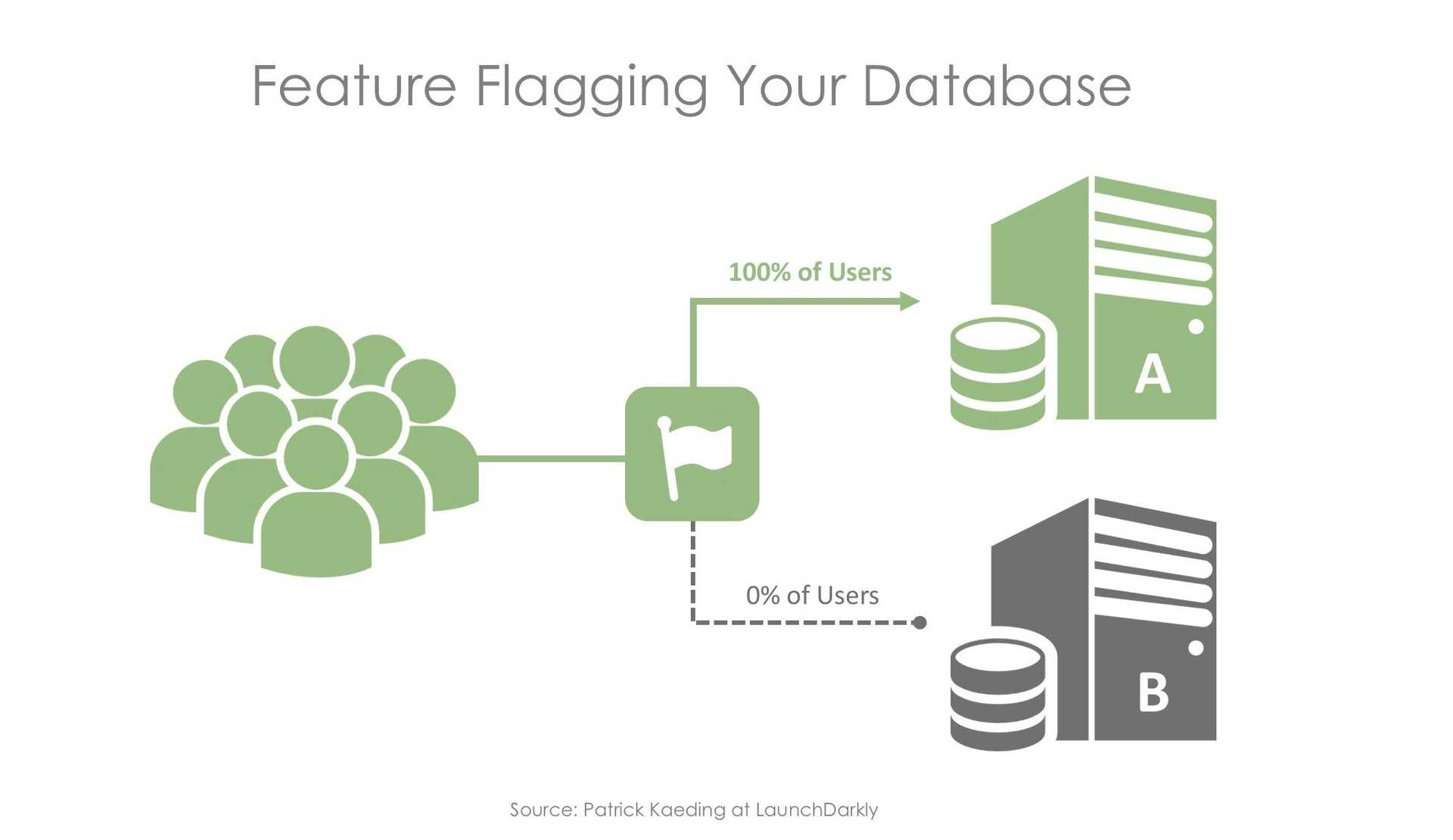

One of the common misconceptions is that feature flags are only useful for new features, or for cosmetic changes. It turns out they are extremely useful for doing things like database migrations. I won’t say that feature flagging your database migration will make everything easy, but it will make it easier to test it with real, live data (for a subset of your user base), and much easier to roll it back if something goes wrong.

Note that the example used here assumes a data model that is never updated–new events are written, and existing events are read, but an event is never updated. The basic idea still works with data that can be updated, but it is a bit more complicated.

The Plan

Suppose you have some DAO code that can read and write events to your database (initially MongoDB). All of your application logic accesses the persisted data through this DAO.

Step one will be to write a new DAO which uses the same interface, but can read and write to DynamoDB (or whatever you choose as your new data store). If there are differences in the way you need to query the data in the new data store, you need to face that at this point. (Sorry, feature flags won’t help you query DynamoDB with the flexibility that you can query MongoDB.)

Feature-flagging your database

Now, you have two implementations of your DAO interface, one backed by Mongo, and one backed by Dynamo. This is where it starts to get fun.

We can use a set of four feature flags to control reading and writing to each database independently. For example, suppose we have this function to save an event:

func storeEvent(evt Event, account ld.User) {

if ldclient.toggle('events-mongo-write', account, true) {

mongoEventsDao.createEvent(evt)

}

if ldclient.toggle('events-dynamo-write', account, true) {

dynamoEventsDao.createEvent(evt)

}

}Copied!

Note that the same event might be saved in both places. This is not an accident! This allows us to start writing events to the new datastore while we maintain the integrity of the old store.

The code that reads the events gets a little more interesting:

func findEventById(id string, account ld.User) Event {

// Check both 'read' flags

shouldReadMongo := ldclient.toggle('events-mongo-read', account, true)

shouldReadDynamo := ldclient.toggle('events-dynamo-read', account, true)

if shouldReadMongo && shouldReadDynamo { // compare results

mongoEvt := mongoEventsDao.findEventById(id)

dynamoEvt := dynamoEventsDao.findEventById(id)

if !reflect.DeepEqual(mongoEvt, dynamoEvt) {

logger.Error.Printf(

"Mongo and Dynamo events differ: mongo: %+v, dynamo: %+v",

mongoEvt,

dynamoEvt)

}

return mongoEvt

} else if shouldReadDynamo { // read from just dynamo

return dynamoEventsDao.findEventById(id)

} else { // read from just mongo

return mongoEventsDao.findEventById(id)

}

}Copied!

So, here we check the two ‘read’ flags, and if both are enabled, then we read the data from both databases, and compare the result. If there is a mismatch, we log an error. This implementation has a bias toward the incumbent datastore (mongo in this example): it will return the value read from mongo when it reads from both stores, and it will also read from mongo any time the dynamo flag is false– it wouldn’t make sense to have both flags turned off and read from nothing.

Rolling it out

Now that we’ve wrapped our data access in feature flags, we can plan the rollout. You can leave the read flag turned off for everyone, and slowly roll out the write flag. Watch performance metrics and error logs. If things look good, roll it out to more users, until all events are being written to both databases.

When you are happy with the write performance, you can start turning on reads to the new datastore. Turn on reads for a small segment of your users, and again, watch the performance metrics and error logs. Specifically be on the look out for the “Mongo and Dynamo events differ” message. But, sleep easy: even if you see that, it hasn’t affected any users. They are still using the data from your old datastore. You can fix any issues and move forward.

Once you have rolled out both the reads and writes to all users, you should migrate all old data from your old datastore to your new one (be sure to do this in a way that is idempotent, so nothing will be duplicated if you migrate an event that was written to both databases).

You can now turn off the read and write flags for the old database, remove all references to all four flags in your code, and you are left with just the new database.

This is not fiction

I didn’t just make up this story to try to tell you how powerful feature flags are. We made this migration here at LaunchDarkly a few months ago, and it went very smoothly. There were one or two bugs that we found using this technique relating to unexpected user data. We saw the logged messages, tracked down the root cause and fixed it very easily, all without impacting our customers.

LAUNCHDARKLY HELPS YOU BUILD BETTER SOFTWARE FASTER WITH FEATURE FLAGS AS A SERVICE. START YOUR FREE TRIAL NOW.