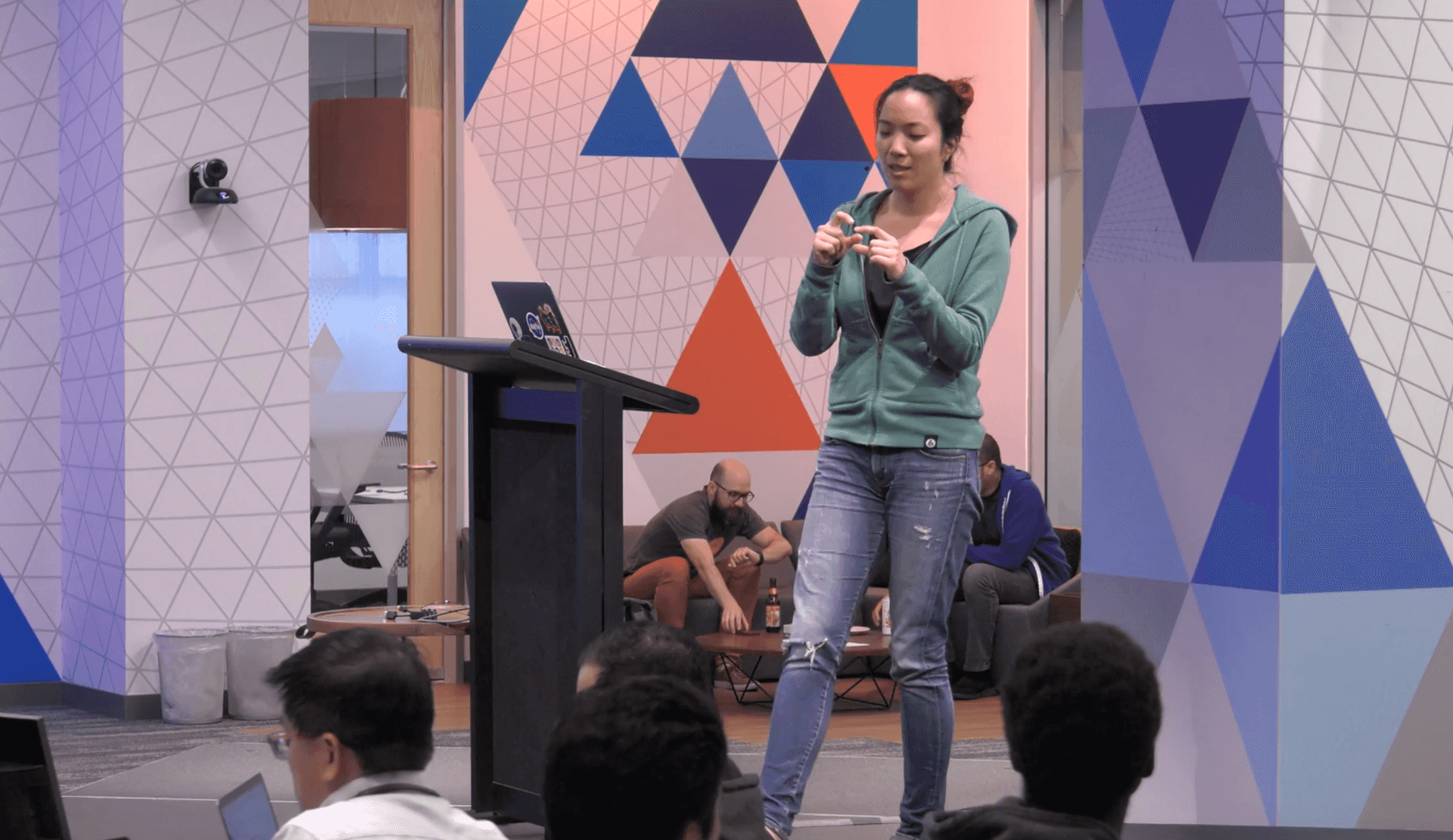

At our Test in Production Meetup in May, we focused on how the culture of failure (avoiding failure, recovering from failure, and learning from failure) has an impact on how we test in production. Christine Yen, CEO and Co-Founder of Honeycomb, gave a talk on how observability can help with "owning code in production."

"One of the things that we at Honeycomb very firmly believe is that in the process of building these bridges, if the first wave of DevOps was all about teaching ops folks to code and automate their work, infrastructures code, then the second wave has to be the other side of the equation. Teaching developers to be comfortable in production and really think, not just, 'Does my code work? Does my code work in its tests?' But, 'Does it work in production?' " - Christine Yen, CEO of Honeycomb

Watch Christine's talk to learn more about how to learn from your code's future–production–to improve the software you ship now. If you're interested in joining us at a future Meetup, you can sign up here.

TRANSCRIPT:

Christine Yen: Hello. Great. Hello, I'm Christine, thank you for having me, and I work on Honeycomb. So today, I really want to talk about how, when we look at production, we can imagine, we can see, we can learn from future potential failures in order to prevent future big failures. In order to understand how things might fail and why and how to prevent them.

I also work at Honeycomb. So thank you Kelly for the introduction, I'm Christine, and I'm a developer. And over the years, our development process has turned into something that has been fairly, there's a lot of steps. There's a lot of comfort, there's a lot of things that we are used to doing in the process of shipping software to our customers. And we're very rigorous about each one of these, we make sure to involve lots of members of our team, and then we ship it and we celebrate, and then more often than not, we sort of just sit back and wait for someone to tell us that it's not behaving the way that we expect.

And that's usually when I, the developer, meet the operator on the team. And this is when the operator comes and knocks on my door and says, "Christine, the thing that you shipped, you should take a look at it again." And that often ends with them walking away grumbling, saying things like this. And this sort of response, an operator being very grumpy at me, tends to result in I, the developer, saying things like this. "Well it worked. Can't imagine what's wrong with the code over on your side of the room."

And the tragic thing about how this plays out, right, is, we're all on the same team. We're all there trying to deliver an experience for our customers. So what happened along the way? What happened to that diligence with which we checked and designed and did code review? How can we, instead of pointing fingers, getting angry at each other, build a bridge, learn from each other, learn from production together, in order to deliver a better experience for our customers?

One of the things that we at Honeycomb very firmly believe is that in the process of building these bridges, if the first wave of DevOps was all about teaching ops folks to code and automate their work, infrastructures code, then the second wave has to be the other side of the equation. Teaching developers to be comfortable in production and really think, not just, "Does my code work? Does my code work in its tests?" But, "Does it work in production? Will it make the ops person only believe in red divs from now on?"

And one of the things that we hold near and dear to our hearts in this first wave, second wave movement is observability. And we're going to talk about observability as not its very formal Wikipedia definition which I've included on this slide for your benefit, but instead a less formal way of saying, what's my software doing? What's happening, maybe why is it not behaving the way that I expect?

And I really like this part of the word especially. Where observability is not a state, I don't think that it's a thing to achieve or have, it's an ability that your team has, that is supported by tools, but ultimately is something that has to be tied to processes and the people on your team, in order to give you the ability to understand what your systems are doing in production. Let's take a look again at this development process.

After we've waited for the exception tracker to complain, heads explosion, we meet the ops folks, and usually, that's the point we look at production and we try to figure out what's going on so that we can go fix our code and repeat that development process over again. But what if instead of just this, instead of just that, what if we looked at prod right after we deploy? What if we looked at prod when we're doing our code review to figure out whether this code makes sense or not?

Whether we're reviewing for the right things, for the right concerns? What if we look at prod when we're writing our tests in the first place? What if we look at prod when we are designing what we're building in the first place? All the way at the very beginning. And using that to inform how we build what we build and why, and how we ship it. I'm going to run through a few different examples here of how we have learned to look at production and tried to either imagine or see these tiny failures in order to prevent bigger incidents down the road.

First, looking at production in order to debug an issue. When folks hear the word debug, usually it's about debugging on your machine. You've got printfs and log lines, this is often one of the very first things that we learn how to do as baby software developers, right? Oh, okay, well, got here, here's a log line to show that we got here. It's great, but in development, doesn't always match your production. But when it does, when we have all that data available, we can usually find out what actually happened.

It gives us basically the ability to reconstruct history and go spelunking to figure out, why did my code do this thing? Walk you through an example. This is something that we hear, where when we hear, "My data isn't showing up in Honeycomb," well, something's wrong. We hold our, it's very important to us that if you send data to Honeycomb, you can query it back within a second, so this is a sign that something's very wrong. Okay. Step one. Can we repro it? Can we do something about it on our machines? No.

Okay. Let's first go figure out why this is happening in production. In this particular incident, we had to add a new field, event time delta sec, what is the difference of time between the time it should have hit our servers and the time it left the client's machines.

And we were able to go, okay, well, let's map this over time for this one particular customer, let's throw in not just average but P95 and the 10th percentile and the median, and by zooming in, looking at production, looking for what was happening with this one account, what was happening with this one piece of data that we knew impacted whether data was available to query or not, we knew more about, we didn't have to just go back to that customer to say, "Hey, I think the problem is on your side."

We were able to go back to them and say, "Ah, well it looks like something's getting backed up before it hits our servers. It looks like it's impacting one availability zone maybe more than the others. And now we can, we'd be happy to help talk you through how you might fix it." And this is the sort of debugging that most developers are used to on their local machines. In their IDEs as a way to really tease apart why something is happening.

And when you're able to do it in production, you don't have to do that guessing ahead of time. You can use production workloads to do that debugging with you, for you. Okay. That's debugging. With building that software itself, not only does looking at production help you debug, it helps us make sure that we're building the right thing, the right software in the first place. And so, it's very easy to just write software that you think should do what you expect it, should do a certain thing.

But after you deploy it, turns out you had some incorrect assumptions. You misunderstood what was normal, what the status quo was, what a normal, typical, what a typical customer workload was. So, okay. Let's look at production to understand what normal is. I love instrumentation and observability because it's almost like you have these debug statements in prod. We've brought it over, we're using, we're gaining this visibility around actual customer workloads, because what we thought was normal in our production workloads from a month ago, six months ago, a year ago, may not at all be true today.

Story here is one in which we wanted to change our sampling policy. Sampling is something that we, our customers will do, in this case, sorry, this is something that we did to protect ourselves. And this is rate limiting, not sampling. So rate limit we just put in place to protect our systems. We wanted to change how this was done. We wanted to make sure that the thing that we were building, this approach that we were taking, wasn't going to overly negatively impact our customers.

So, okay. Few different algorithms we could take, few different architectures we could explore. Instead of making the change, believing that it would be the right approach and shipping it, what we did, this is 2016, what we did is we had the old algorithm in place, go to the new algorithm, didn't actually send, use the results of that new algorithm. But we were able to push production traffic through it, measure the results, and use it to verify, okay, this approach that we're taking, this code that is barely even in code review, it would work in this way, great. Looks good, let's ship it.

And that helped make sure that once we shipped it, we knew how our system was going to impact our customers. We knew that customer A would see a few more of their requests come through, we knew that customer B would see fewer of their requests coming through, and we knew how to respond and what to look for once we flipped it on for the whole population. Another thing that we can do, we are at a testing in production meetup. All of you are very comfortable, familiar with the gospel of not being beholden to what happens pre-production.

But I'm sure I believe a lot of you have experienced skepticism. Where people are like, "Oh, test in production? Well, I like my test before production too, and you can't drop that, you can't set that by the wayside." And it's true, right? Test in production and also test before production. But, what a lot of people don't think about when they're busy sniffing and making grumpy noises at you, is that looking at production can even help people write better pre-production tests. Right? With pre-production testing, often you're in this state where you're guessing at test cases to immortalize in your CI system.

You're guessing at what things to protect against, what regressions might occur, well, what better way to think about test cases than looking at what your system is dealing with today? Understanding what the boundaries are of the, this graph is showing payload size. So understanding what the largest payload sizes we're dealing with today is, setting that as a immortal test case, and knowing that in the future, worst case scenario, we are protected against payloads of 500 columns or less.

And while I like this use case, usually in talking to someone, bringing this use case up is the best way of saying, "And this is why pre-production tests are never going to be enough." Right? You're taking something, you're immortalizing it, and assuming that it will be enough for your ever-evolving system. Which is why testing in production is another way that we can either guess at, anticipate, or simulate these mini failures in order to make sure that we're shipping, we ultimately ship the right thing.

This slide I feel like is table stakes for this crowd. But again, for folks who are a little bit less familiar or less comfortable with testing in production, it's about, it all depends on when you know how your, what the expected results are. And I like calling this slide out, and this graph out in particular. This was an example of us making some changes to our query engine. We're making some changes to query engine.

We were very nervous about impact on performance, impact on correctness, and by pairing it with feature flags, sending the results and the values of all of our feature flags in along with the pieces of the code that were capturing performance characteristics, we were able to take the same latency graphs, the same volume graphs that we looked at to generally gauge the health of our query engine, this very performance-sensitive part of our infrastructure, and break it down by something that was ephemeral.

And also something that was actively being moved around by our engineer. And the best part about this was, right, when you test in production, you can target who it's going to impact. So we were able to say, well, let's test it on a demo data set first. And let's see how it fails. Let's see how it breaks, let's see whether there's a performance impact, okay, at this point we turned the flag on, these graphs jumped up. Holy cow, is this a failure?

Do we care? Do we understand why this happening? And all these questions are ones that we can be asking even before that code hits production for everyone. And the act of looking at production and understanding how to ask these questions of, this is what I expect, this is what I see, and why, are things that just form this great virtuous feedback cycle of do you understand what your code will do when it's out there in the wild?

Which brings us to the final stage. After you deploy, often you wait for, this is the wait for an exception tracker to tell you when something's gone wrong phase. There's a lot of tools out there already that will tell you things about how your software's behaving, whether it's within an acceptable threshold, whether the graph that you're used to watching on the wall has deviated from what you expect. But one of the things that I found as a developer is that a lot of those graphs, a lot of these traditional monitoring tools didn't speak the language that I needed to really map it to my code.

We could rewind time, back in 2013 I was using, I was an engineer on a team that was using Graphite, and a thing that would happen all the time is an ops person would come to me and say, "Christine. This code that you shipped? Cassandra rates are up. Fix it." And I'd just be like, I don't know what I did that caused this arbitrary metric over here to increase.

I know endpoints, I know customers, I know certain operations, but Cassandra rates, that means nothing to me. I'm a developer, that doesn't map to the entities in my code. An example of this is, what would have made sense is, "Hey Christine. After you pushed your deploy, this build with only your code in it caused latency to go up on this particular endpoint for our largest customer." Oh great, okay.

Well that tells me as a developer, immediately, how big of an issue it is, it tells me where to start looking for it, and a little bit about how to start reproducing this. How to start investigating, and how to start understanding how to make Cassandra rates go down. This particular graph is something that shows the number of servers that are running a particular build. And seems like a pretty simple graph, right?

Should be pretty stable, for whatever reason there's a, one particular, one node that is still running on an old build. But this incredibly simple graph tells me, my code is out there, if I see any inconsistency, it might be because there's these other servers, and also, this also shows me how gradual this rollout is. And the reason that's helpful is in this particular example, I was sitting and, again, making changes to our performance-sensitive query engine, and I was pushing a change and watching for my change to go out, that should have had no impact on performance.

Around 9 p.m. something went out that had a big impact on performance. But because we were able to break down by build, able to really quickly say, "Oh, hey, looks like the thing that came out in the build after me had this change, wasn't my change, but I know whose it is, I can very clearly see that these are related, and we can immediately see it roll back." And by starting to have these production tools speak my language, so I could understand when things failed and why, and start to map them back to the thing that I was familiar with, it means that my development process involves less guessing about why something went wrong.

I can go, I can investigate, and I can be confident in order to continue that virtuous cycle, that flywheel, instead of having to have ops come and yell at me every time. Because that's what we all need to do, right? This is the very kumbaya part of this talk. Working together as a team to deliver software to our customers, we all need to work better together.

And what that means is we all need to be doing a better job, forming a hypothesis about what our code will do, or did what it should have done, putting the instrumentation or making sure the instrumentation is there in place to verify that, run queries, look at graphs, do whatever in order to validate or invalidate that hypothesis, and take action. Because without the ability to actually look at production and understand, you're sort of just jumping from one to four, hoping that you were right along the way.

And this is how we will turn from dev and ops fighting each other into the very cute cuddly animal photos that power the internet today. Because instrumentation and observability shouldn't just be things that are the end of the development cycle. Testing in prod shouldn't be something that happens after everything else. It's got to be something that is continually folded in, in order to give us continual observability into what's happening with my system.

And if we stop writing things and doing everything based on intuition, we ask lots of questions, and we ask that question of why, and we expect to actually find out the answer, that's how we're all going to ship better code, improve our culture and embrace failure rather than being scared of it. Thank you.

.png)