Guest post by Isaac Mosquera, Armory CTO and Co-Founder.

My co-founder DROdio likes to say “Business runs on relationships, and relationships run on feelings“. It's easy to misjudge the unseen force of human emotions when changing the culture of your organization. Culture is the operating system of the company; it's how people behave when leadership isn't in the room.

The last time I was part of driving a cultural change at a large organization it took over three years to accomplish with many employees lost—both voluntary and involuntary. It's hard work and not for the faint of heart. Most importantly, cultural change isn't something that happens by introducing new technology or process; containers and microservices aren't the solution to all your problems. In fact, introducing those concepts with a team that isn't ready will just amplify your problems.

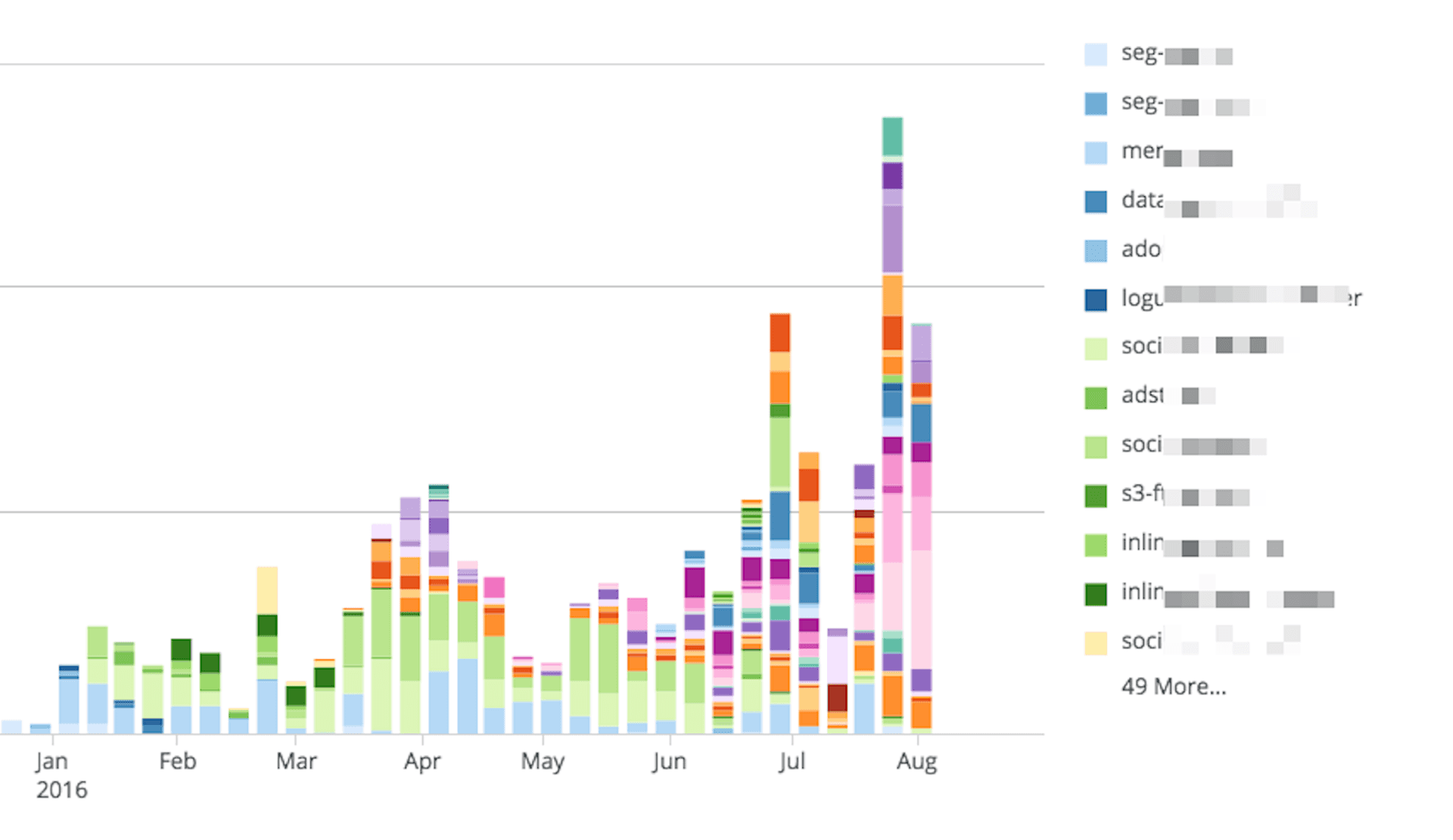

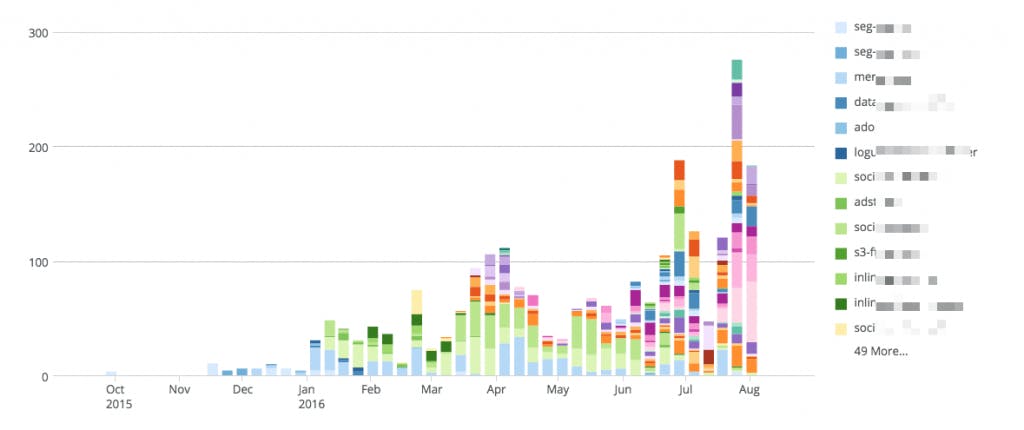

Change always starts with people. When I was at that large organization, we used deployment velocity as our guiding metric. The chart below illustrates our journey. The story of how we got there was riddled with missteps and learning opportunities, but in the end we surpassed our highest expectations by following the People → Process → Technology framework.

People

Does your organization really want to change? It's likely that most people in your organization don't notice any major issues. If they did, they probably would've done something about it.

In that big change experience, I observed engineering teams that had no automated testing, no code reviews, suffered from outages, infrequent deployments and, worst of all, an ops vs devs mentality. There was complete absence of trust masked by processes that would make the DMV look innovative. In order to deploy anything into production, it took 2-3 approvals from Directors and VPs who were distant from the code.

This culture resulted in missed deadlines, creating new services in AWS took months due to unnecessary approvals. We saw a revolving door of engineers, losing 1-2 engineers every month on a team of ~20. There was lack of ownership—when services crashed, the ops team would blame engineers. And we experienced a “Not Invented Here” mentality that resulted in a myriad of home grown tools with Titanic levels of reliability.

In my attempt to address these issues, I made the common mistake of trying to solve for them before I got consensus. And I got what I deserved—I was attacked by upper management. From their perspective, all of this was a waste of their time since nothing was wrong. Also, by extension, asking to change any of these processes and tools, I was attacking their leadership skills.

Giving Your Team A Voice

The better approach was to fix what the team thought was broken. While upper management was completely ignorant to these issues, engineers in the trenches were experiencing the pain of missed deadlines, pressure from product and disappointed customers. For upper management, ignorance was bliss.

So we asked the team what they thought. By surveying them, we were able to quantify the problems. It was no longer about me vs upper management. It was the team identifying their biggest problem and asking for change—the Ops vs Devs mentality. We were one team, and we should act like it.

So what are some of the questions you should ask in your survey? Each organization's surveys should be tailored to their needs. But we recommend open ended questions, since multiple choice questions typically result in “leading the witness”. Some questions you might want to consider include:

- What are the biggest bottlenecks in getting the most time?

- What is stopping you from collaborating with your teammates?

- Are you clear on your weekly, monthly and yearly objectives?

- If you were the VP of Engineering what would change?

- What deployment tools are you using to deploy?

After summarizing your survey feedback, you'll have a rich set of data points that nobody can argue with because they would just be arguing with the team.

Picking Your One Metric

Now comes the hard part: selecting a single metric that represents what you're trying to change. The actual metric actually doesn't matter, what matters more is that it's a metric that your team can rally your team around.

For us, the “Ops vs Devs” were causing significant bottlenecks, so we chose number of deployments as our guiding metric—or as we called it “deployment velocity”. When we started measuring this, it was five deployments per month. After a year of focusing on that single metric we increased it to an astounding 2,400 deployments per month.

Process

If culture is a set of shared values by your organization, then your processes are a manifestation of those values. Once we understood that the “Ops vs Devs” culture was the focus, we then wanted to understand why it was there in the first place.

As it turns out, years earlier there were even more frequent outages, so management decided to put up gates or a series of manual checklists before going to production. This resulted in developers having their access to production systems revoked because they were not trustworthy.

Trusting Your Developers

I don't understand why engineering leaders insist on saying “I trust my developers to make the right decisions,” while at the same time creating processes that prevent them from doing so and turning talented engineers unhappy. To that end, we began by reinstating production access to all developers. But this also came with a new responsibility: on-call rotation. No longer were the operations team responsible for developer mishaps. Everyone was held responsible for their own code. We immediately saw an uptick in both deployments and new services created by making that change in process.

Buy First, Then Build

We also made the decision to buy all the technology we could so development teams could focus on building differentiated software for the company. If anyone wanted to build in-house, the decision and process had to be dramatically cheaper than buying. This process change not only had an impact on our ability to add value to the company but it actually made developers much happier in their jobs.

A True DevOps Culture

What formed was a new team which was truly DevOps. The team was created by developers who truly were interested in building software to help operationalize our infrastructure and software delivery. New processes were created to get the DevOps team involved whenever necessary, but they alone were not responsible for SLA's or uptime of developer applications. A partnership was born.

Technology

Too many engineers like to start a process like this by finding a set of new and interesting technologies, and then forcing them onto their organization. And why not? As engineers we love to tinker. In fact, I made this very mistake at the beginning. I started with technical solutions to problems only I could see, and that got me nowhere. But when I started with people and process first, the technology part became easier.

Rewriting Our Entire Infrastructure

Though things were getting better, we weren't out of the woods yet. We lost a core operations engineer who didn't share the process to deploy the core website! We literally couldn't deploy our own website. This was a catastrophic failure on the engineering team, but it was also a blessing in disguise. We were able to ask the business for 6 weeks to fix the infrastructure so we would never be in this position again. We stopped all new product development. It was a major hit to the organization, but we knew it had to get done. We ultimately moved everything to Kubernetes and had massive productivity gains and cost reduction.

Replace Homegrown with Off-the-Shelf

In this period of time we also moved everything we could into managed services by AWS or other vendors. The prediction was the bill would be incrementally larger, but in the end we actually saved money on infrastructure. This move allowed the team to focus on building interesting and valuable software instead of supporting databases like Cassandra and Kafka.

Continuous Deployment and Feature Flagging

We also decided to rewrite our software delivery pipeline and heavily depend on Jenkins 2.0—mostly due to a suitable solution not being available like Spinnaker. We still got to throw away much of our old homegrown tooling, since the original developer was no longer there to support it. And while this helped us gain velocity, ultimately we needed to have safer deployments—when our SLAs started decreasing, we were exposing our customers to too much risk. To address that issue, we built our homegrown feature flagging solution. This too, was because off the shelf tools like LaunchDarkly didn't exist at the time (recall our preferred approach to build vs buy). The combination of the tooling and process allowed us to reach deployment velocity that surprised even ourselves.

Results

The chart below speaks for itself. Each new color is a new micro-service. You'll notice we started with a few large monoliths and then quickly moved to more and more microservices because the friction to create them was so small. In that time, deployment velocity went way up! Most importantly the business benefited too. We built a whole new revenue stream due to our newfound velocity.

Approaching these changes from the people first made the rest of this transition easier and enjoyable—our team was motivated throughout the entire journey. In the end, the people, process and tools were all aligned to achieve a single goal: Deployment Velocity.

* * *

Isaac Mosquera is the CTO and Co-Founder of Armory.io. He likes building happy & productive teams.