The technology acceptance model (TAM) is a concept that has been around since 1989 to try to explain how people adopt and accept a new technology. According to this model, users make a decision to adopt based upon two primary factors:

1. Its perceived usefulness or, in the words of the model's creator, Fred Davis, "the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance their job performance."

2. Its perceived ease of use or, again from Davis, "the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would be free from effort."

Let's assume you're here because you've read about what feature flags are and why they are useful. You've decided that they can solve real problems for you. Perhaps you've already adopted feature flags via a homegrown system or a feature management platform like LaunchDarkly and found them easy to implement in your code. However, you may still find that moving that adoption forward isn't always easy. You've hit the software development equivalent of Newton's First Law of Motion about inertia, which is that it can be tough to change the workflow of a software engineering team in motion.

Change is difficult, especially when the process of building an application doesn't stop to let you and your team adjust to the new reality of development using feature flags. So in this post I want to lay out a common pattern I hear when I talk to developers about their adoption of feature flags that may help you in thinking about and planning your own.

This isn't a formal plan, or even the "right way" to adopt feature flags (the right way is just the way that works for you successfully after all). It's just a common path that teams seem to follow.

Stage 0: The Recognition

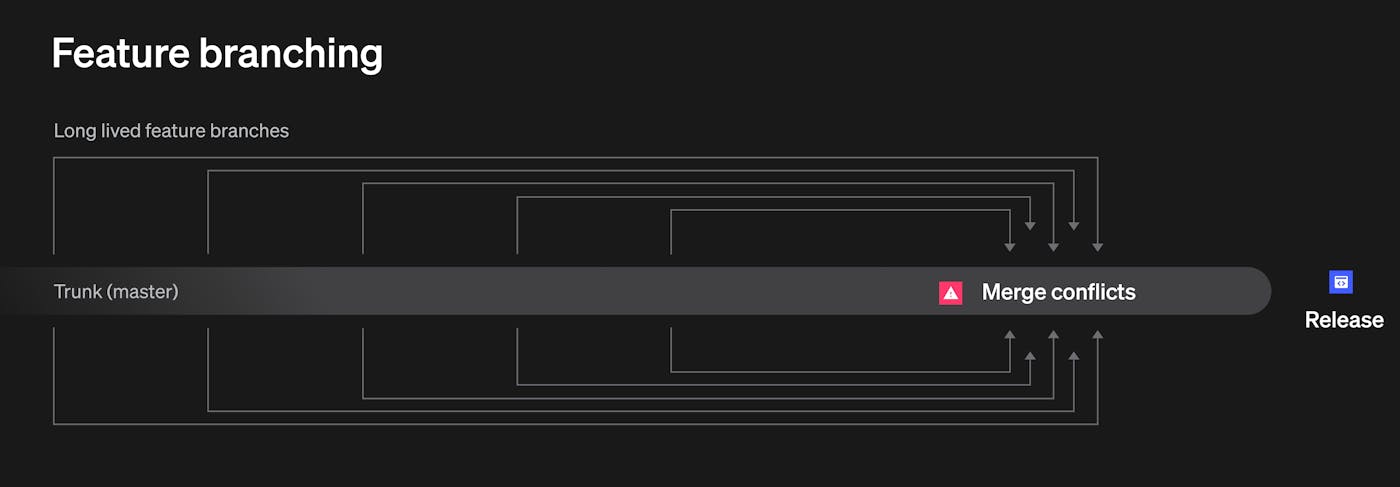

Since you are reading this article, it's probably safe to assume that you've already begun your journey. Still, it's worth noting that in many (if not most) cases, the decision to adopt feature flags comes from the engineering team. This is typically because the current branching strategy has become unmanageable. There are too many branches, too many environments and the process of merging these into main has become difficult and error prone.

The engineering team starts looking into concepts like trunk-based development as a means of solving this problem. A key component of successfully adopting trunk-based development is feature flags. Implementing feature flags seems like a light lift (i.e. it's perceived as both useful and easy to use in TAM terms).

But, as we'll discuss, even if the engineering team drove the adoption, there is still a lot of work to be done to ensure that this adoption is successful and solves the issues that it initially aimed to solve.

Stage 1: The Boolean Era

While boolean flags are conceptually simple, this stage is typically the longest and most difficult part of the process because it involves changing the way you and your team operate.

The basics of trunk based development seem relatively simple:

- I want a feature turned on for me in my local environment while it is currently under development.

- I also want to be able to check in to the main branch frequently, to keep the code in sync, but have the feature turned off for everyone else until it is ready.

A simple toggle (i.e. on/off switch) works fine for this purpose. Easy, right?

The answer is yes...and no. Implementing a boolean flag is easy whether you are using a homegrown flag system or a platform like LaunchDarkly.

let showNewFeature = client.variation('show-new-feature', { key: 'guest', false});

if (showNewFeature) {

// run this code

}Managing the transition

The hard part is changing the way everyone works. Even if everyone is on board with the fact that the prior branching strategy was unsustainable, actually changing habits can be difficult. You can't just drop a tool on the team and hope that they use it.

This is complicated by an uncertainty over what features should be flagged. Perhaps they think flags are only for major features that will take weeks or months of development, whereas the feature they are currently working on is minor and should be done in a day or two anyway, so why bother? This scenario repeats itself indefinitely and thus the process never really changes in a meaningful way.

To help prevent this, it is good to set expectations up ahead of time and be sure everyone is on the same page with the shift in development practice. Try to eliminate any potential roadblocks by establishing a naming strategy, and perhaps even a cleanup process for flags once the feature is released. While these decisions may seem small, they can add cognitive load that can dissuade adoption (i.e. the "old way" has problems, but they are problems you've become accustomed to dealing with).

It's also important to establish a check-in cadence with your team to specifically review the feature flag adoption process to ensure there are ample opportunities to address any questions or concerns as well as set a marker for evaluating progress. Another, more hands-on apprach would be to initially set up code reviews prior to merges to ensure and evaluate flag usage.

Stage 2: The Great Configuration

Once your team becomes comfortable with flags for local development and testing with frequent merges into main (i.e. trunk-based development), they usually begin thinking beyond the boolean. They come up with ways to use multivariate flags, which are flags that can hold more than the standard two (true/false) variations.

Another common capability is passing down configuration details as strings, numbers, or JSON values. This can enable both testing and implementation of more complex functionality. For instance, what if you want to test some database changes locally that are different than the default configuration? You could even pass the database configuration string via a flag.

@app.route("/users", methods=["GET", "POST"])

def users():

fallback = '{"dbinfo":"localhost","dbname":"localdb"}'

ldclient.set_config(Config(LD_KEY))

context = {

"key": "guest"

}

dbinfo = ldclient.get().variation('dbDetails', context, fallback)As another example, at LaunchDarkly we used a series of dependent flags that contained design configuration details to launch our rebrand in secret in late 2021.

Advanced targeting

Adding multi-variate flags to manage application configuration also tends to lead developers toward ideas for more advanced targeting than simply "on for me, off for everyone else," and towards a scenario where the aspects of the application depend upon contexts.

For example, you could set up contexts that enable certain application functionality or load different configurations depending on the environment the application is running in, while also showing in testing features to Sandy because she's part of the QA team.

{

"kind": "multi",

"environment": {

"key": "environment-id-123abc"

},

"user": {

"key": "user-key-abc123",

"email": "sandy@acmecorp.com"

}

}Another example might be expanding your targeting context to include device type details that you might use to target a specific, physical, device type with these same changes ("I want only MacOS devices to receive the updated database details"), or by extending the user context to include the user's timezone, so you can roll a change out regionally.

{

"kind": "multi",

"environment": {

"key": "environment-id-123abc"

},

"user": {

"key": "user-key-abc123",

"email": "sandy@acmecorp.com"

"timezone": "Pacific"

},

"device": {

"key": "user-device123",

"platform": "MacOS",

}

}An even more advanced example would be to use targeted feature flags to manage entitlements. In this scenario, you could have a segment of users from Acme Corp, that are on the "Performance Tier" and receive flag variations containing configuration values that tell the application what functionality their subscription has enabled.

{

"kind": "multi",

"environment": {

"key": "environment-id-123abc"

},

"user": {

"key": "user-key-abc123",

"email": "sandy@acmecorp.com"

"timezone": "Pacific"

"tier": "Performance"

},

"device": {

"key": "user-device123",

"platform": "MacOS",

}

}Stage 3: The Expansion

In this stage, you're well beyond feature flags being just an engineering tool. Q&A teams can now have access to flags to test new functionality, and with the additional example of managing entitlements, the Product team is likely involved in rolling new capabilities out to teams. You're well into feature management territory now.

If feature flags are a engineering tool, feature management is the practice that moves teams beyond just flags and toggles, and scales the management across the organization.

This can be an empowering stage even for the engineers.

- Need to add a user to the beta program? The Product Manager can add a user to our beta targeting segment.

- Does a new feature need to launch in alignment with a marketing campaign? The Product Marketing Manager is empowered to turn the feature on for everyone when the campaign goes out.

- Want to turn on special debugging output to assist when a user is having an issue? The Support Engineer has the ability to target a customer with a debugging feature that enables them to solve the issue quickly.

These are just a few examples, but the point is: a lot of tasks that once required direct engineering involvement and time, no longer need to.

(One of the key benefits of a service like LaunchDarkly at this stage is support for multiple environments to be sure that the flag changes of different teams or team members aren't impacting others.)

Stage 4: The Experimentation

At this point, you're doing trunk-based development, using flags for configuration, and leveraging advanced context targeting techniques. Teams across the company are also utilizing feature management to enable them to make their jobs easier without adding to the engineering team's backlog.

Along the way, you've started doing percentage-based and/or targeted rollouts (maybe by timezone, like our previous example), ensuring that your features are launched with minimal risk (but you're covered by kill switches just in case anyway).

But how do you know that you're releasing the right features? Experimentation.

Experimentation allows you to make hypotheses about how a feature will behave or how users will behave and validate those with actual data. This is relatively straightforward on the frontend of an application. For example, you enable some feature and see if people use it. Or you change some call to action (CTA) text and see if it triggers more click-throughs. Those are powerful tools to assist in decision-making.

However, where it gets really interesting for the engineering team is server-side experimentation. For example, did the changes you made positively impact the applications performance as you expected? Or, as Charity Majors of Honeycomb shows, does switching to AWS Gravitron get the performance improvement and reduced AWS bill that you anticipated? Using server-side SDKs and experimentation together can enable you to test things beyond just the user interface (UI).

Conclusion

Don't worry if your teams path diverges from the one I've laid out above. The goal here was simply to offer some potential milestones to plan and measure against. Nonetheless, if I can leave you with one last piece of advice, it's to take your time and not rush the process. Trying to jump to stage three or four before you're ready can lead to frustration and possibly failure, especially if your team is new to feature flags and trunk-based development. But a steady and measured approach to feature flag adoption will likely lead to success.

.png)